The beginning of the 21st century has seen a surge of citizenship tests introduced as one of prerequisites for obtaining citizenship in European states. The aim of this paper is to briefly present the debate about liberal and illiberal aspects of citizenship tests. My main contribution is an evaluation of the Czech citizenship test in light of the ongoing debate by applying Michalowski’s (2011) content analysis method on the Czech case.

(This essay was submitted in Autumn Semester 2015 for the class “Citizenship Regimes in Europe: Norms and Practices” led by Szabolcs Pogonyi at the Central European University in Budapest.)

(Il)liberalism of citizenship tests

The heated debate was started by the Dutch test which has been seen as imposing “ill-defined ‘Dutch norms and values’ on (muslim) immigrants” (Joppke 2010, 1). Critics saw it as a movement of definition of citizenship from a thin civic definition (represented by questions about politics) closer toward an ethnical thick version (questions about culture). On the other hand, Joppke (2010, 4) argues that standardization of tests may be a win in liberality if compared to the infamous interview guidelines of Baden-Württemberg. According to von Koppenfels (2010, 12), the introduction of citizenship tests may mark a recognition of European states that they are immigrant states. But these two arguments seem to be the only ones evaluating citizenship tests positively.

Most of the academic debate is concentrated on the question how to distinguish liberal from illiberal aspects of citizenship tests. Joppke (2010, 2) suggests defining the threshold as based on Kant’s distinction between morality and legality, which Michalowski (2010) translated into the difference between the questions of “What is right?” and “What is good?”. Therefore a liberal state has to accept also illiberal people (people whose concept of good is illiberal) and cannot scrutinize their inner dispositions. The state is allowed to act only if their behaviour conflicts with law (what is right according to a state).

Therefore a liberal state has to accept also illiberal people (people whose concept of good is illiberal) and cannot scrutinize their inner dispositions. The state is allowed to act only if their behaviour conflicts with law (what is right according to a state).

Therefore Michlowski (2010, 6) stresses that “formulation matter” and accordingly the German citizenship test question “Who is not allowed to live together as a couple” is referring to law and defines a homosexual cohabitation as legal – since it speaks about legality the question is also liberal. In contrast the Dutch test question referring to social norms “the candidates knows that concubinage (also of same-sex partners) is accepted in Netherlands.” is illiberal since it oversteps legal framework and also the Rawlsian “overlapping consensus” necessary for a liberal society. Because not all Dutch social and religious groups accept homosexuality and it is also not necessary for a liberal democracy. Thus Michlowski suggests that it is important to evaluate how a citizenship test presents competence of a state in regulating a multicultural society (e.g. comparing active Dutch state in moderating conflicts to the US stance of seeing them as a private affair).

In contrast to the previous approach, Kostakopoulou (2010) suggests “zooming out” from the content of tests toward their context. What was the political discourse during introduction of the tests – was not its primary aim to limit access to citizenship? As Carrera and Guild (2010, 37) points out, some states (Germany, Denmark, the Netherlands, Austria) introduced a test already for an acquisition of a permanent residency. Similar acts indicate a levelling-up of hurdles although the aim may be to uphold liberal values – as Orgad (2010, 21) notes “some European states embrace illiberal policies that violate the same values they seek to protect”. There is a considerable consensus among scholars (Joppke 2010, Carens 2010) that also the context of test matters: whether the test questions are available so that it is possible to prepare for the test or if it is possible to retake test and how high are the cost

In what Joppke (2010b) calls a maximalist position this argument can be extended saying that borders (therefore also distinction citizen vs. non-citizen) are per se illiberal since they limit freedom and thus “the most liberal citizenship test is none at all” as Carens (2010) claims. As a maximalist, Joppke labels also the “Foucaldian” concerns of Groenendijk and van Oers (2010) that citizenship tests are exercised by nation-states to discipline and standardize, even humiliate immigrants and turn them into “perfect citizens”. This position is in contrast with Joppke’s minimalist position which recognizes that treating non-citizens differently does not create a double standard since it is a substitute for a state education which immigrants missed and is obligatory for its citizens. The main minimalist argument is based on the already mentioned “formulation matters” specification. After summarizing the debate about how to evaluate citizenship tests I will proceed with the Czech example

Joppke’s minimalist position which recognizes that treating non-citizens differently does not create a double standard since it is a substitute for a state education which immigrants missed and is obligatory for its citizens

Context of the Czech citizenship test

The citizenship test was introduced in 2014 with the new citizenship law of the Czech Republic. This law enabled dual citizenship and made easier the naturalisation of second generation of immigrants – on the other hand as the officials admitted naturalisation became stricter (idnes.cz 2012, radio.cz 2012, mipex.eu 2012). Instead of a max. 30 min interview with an office a language test on level B1 is required, the citizenship test was introduced, and a newly added condition is also that the applicant cannot be heavily depending on state’s welfare benefits (if he/she is in active working age). An applicant also has to prove a permanent residence of five years (three years for EU/EEA citizens), and has to show size and source of his/her income and that the taxes has been paid properly in last three years (migrationonline.cz 2013).

The NGOs welcomed the already mentioned liberalisation but criticized heavily the following aspects: firstly, there is no legal right on citizenship even after fulfilment of all preconditions; secondly room for an administrative discretion became even bigger since it is up to the officers in the Ministry of Interior to decide whether „the applicant is integrated into the society in the Czech Republic, in particular as regards integration from family, work and social perspectives.” (according to the explanatory memorandum” (migrationonline.cz 2013); and thirdly the decision of intelligence services if the person poses a risk for the Czech state can not be repealed by an appeal to a court – this according to NGOs enables security services to blackmail applicants.

The Czech Republic feels obliged to follow the international trend of introducing dual citizenship which leads to liberalisation. On the other, hand it does not want to liberalise “too much” and therefore tries with building up of additional hurdles, to restrict liberalisation.

All those circumstances seem to support the argument of an EUDO expert that the new law can be evaluated as “Restrictive Liberalisation” (mipex.eu 2012). The Czech Republic feels obliged to follow the international trend of introducing dual citizenship which leads to liberalisation. On the other, hand it does not want to liberalise “too much” and therefore tries with building up of additional hurdles, to restrict liberalisation. Indeed, the liberalising effect of dual citizenship was considerable and in 2014 the number of persons who acquired Czech citizenship doubled to 5000 persons in comparison to the previous year (praguepost.com 2015). Furthermore what seems to me to be the most shocking part of the new citizenship law is part of the explanatory memorandum which specifies social integration that is clearly against liberal values since the condition is: “(e.g. engagement in [civil] society, activities in civil associations, and the extent of his/her involvement in social life, and acceptance of cultural traditions).” (migrationonline.cz 2013, emphasis mine). Therefore one of THE previously mentioned conditions is violated since the state asks applicants to accept not only laws (what is right), but to accept also the cultural conception of what is good. I will discuss it later in the context of the test questions to enlighten which traditions seem to be so important to the Czech state (page 7).

Therefore one of THE previously mentioned conditions is violated since the state asks applicants to accept not only laws (what is right), but to accept also the cultural conception of what is good.

To understand the context of the Czech test it is worth looking at who wants to become a Czech citizen and the naturalization numbers. The highest number of naturalizations happened before the accession to the EU in 1999-2004 when it was around 5000 naturalizations per year, in 2005-2013 it dropped to around 2000 successful applicants and went up back to 5000 after the introduction of dual citizenship in 2014 (statistics from eudo-citizenship.eu 2015, czso.cz 2015). An important aspect is that more than half of successful applicants in 1999-2013 were naturalized because of a declaration, which is a process aimed at emigrants, descendants (up to grandchildren) of Czechs living abroad and citizens of former Czechoslovakia. In 2011 the ratio has finally changed and more Slovaks were naturalized in standard process than gained citizenship by a declaration. Thus it is possible to expect that the number of applicants claiming citizenship because of dissolution of Czechoslovakia in 1993 will decrease. The number of applicants from Czech(oslovak) descendants will also decrease although probably by a slower pace. After explaining dynamics of citizenship acquisition, let’s take a look on applicants. The biggest group of successful new Czech citizens are since 2009 Ukrainians (948 in 2013) who overtaken second Slovaks (270 in 2013, 127 by declaration). Among biggest group belong also Russians and Vietnamese (around 160 in 2013, Vietnamese are the most different ethnic minority and came to the country already during communist period and after the Velvet Revolution).

Content of the Czech citizenship test

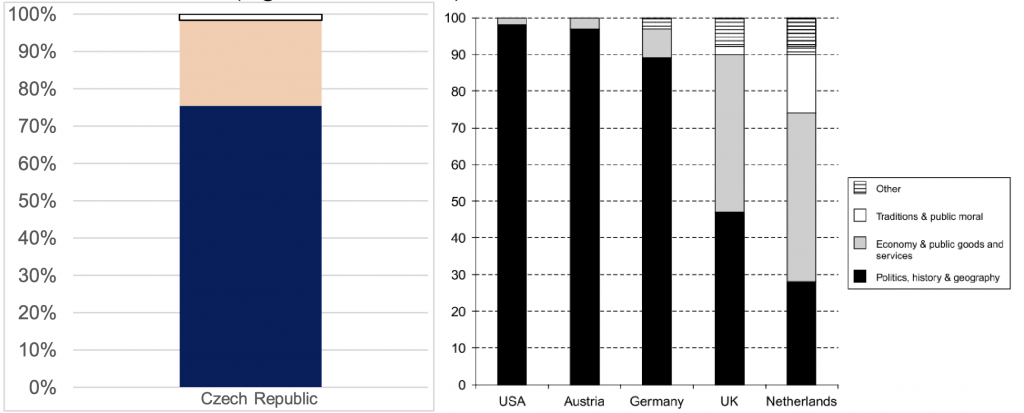

My content analysis is evaluating the Czech citizenship test (all 300 questions and answers are available freely at the obcanstvi.cestina-pro-cizince.cz website) based on Michalowski’s (2011) article. Michalowski made a content analysis of citizenship test questions in five countries and found that tests in the UK, USA, Austria and Germany are liberal – but not in the Netherlands. Michalowski divided questions into the three main categories: A) Politics, history and geography, B) Economy, public service and its financing, C) Traditions and public moral. Those categories were further divided into a subcategories (marked with numbers to contrast overall categories with letters A, B, C). In the Figure 1 you can see an overall distribution of tests questions of the Czech citizenship test (Figure 1a) in comparison with the table from Michalowski’s article (Figure 1b, 2011, 758).

Figure 1b Citizenship tests in Michalowski (2011, 758)

The Czech test’s proportions of A) Politics, history and geography and B) Economy, public service and its financing questions lie between Germany (with more A) Politics and less B) Economy than the Czech test) and UK (with less A)Politics and more B) Economy). Questions about C) Traditions and public morale in the Czech test are proportionally quite small as it is the case of both Germany and the UK. I omitted the category Other in my evaluation, since I rather put all questions in one of three categories to evaluate them all.

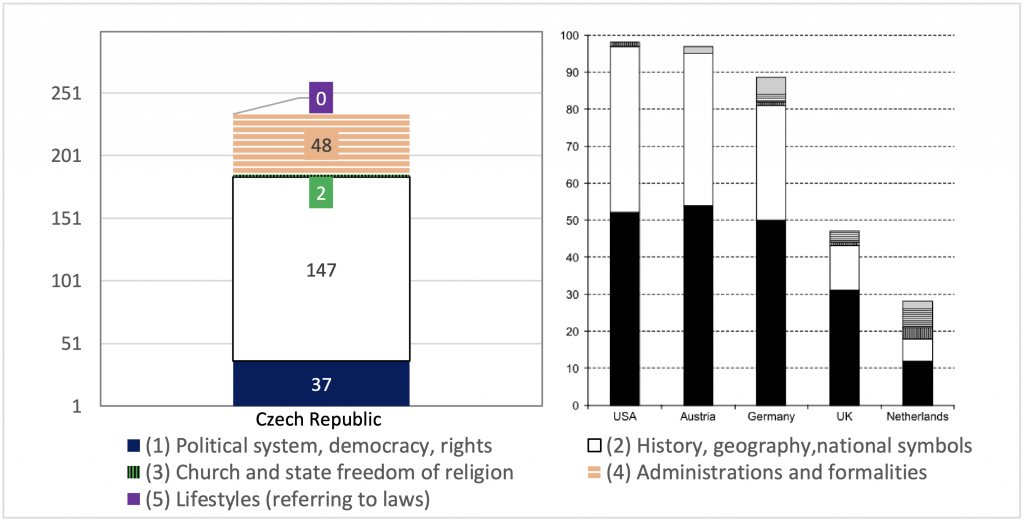

We get more telling results if we take a look at the category A) Politics, history and geography (Figure 2) and its five sub-categories. We can clearly see that in the Czech test in contrast to other tests the subcategory 2. History, geography, national symbols clearly dominates. The second biggest subcategory in the Czech test is 4. Administrations and formalities which is negligible in all states researched by Michalowski. Quite interesting is also that the proportion of the 1. Political system, democracy, rights subcategory is similar in the Czech Republic and the Netherlands and accounts for around 10% of all questions in the tests.

(number of questions), Figure 2b: Same (sub)categories in Michalowski (2011, 759)

At the same time, looking even closer on the questions from the subcategory 1. Political system, democracy, rights shows that there is not just a quantitative but also a qualitative difference. Michalowski (2011, 754) coding examples of this subcategory are those five: What type of constitution does the UK have? What are the two major political parties in the USA? What is the function of elections in a democracy? When did women receive the right to vote? What are the minimum ages for buying alcohol and tobacco? These questions are mostly concerned with political rights fulfilling the idea that obtaining citizenship means foremost full inclusion into a national polity. But the questions in the Czech test are rather concentrated on names (not even function!) of institutions as this example show: Ms. Novotna wants to attend a meeting of the Chamber of Deputies. Which state office visit? A) The Czech Parliament. B) The Office of the Government. C) The Constitutional Court of the Czech Republic. D) Ministry of Justice. (expats.cz 2014). Based on this example I divided the subcategory 1. Political system, democracy, rights into three subgroups: I) Institutions, II) Political rights and III) Integration (concerning integration into NATO and EU). My findings are that 29 questions belong to the I) Institutions, two to the II) Integration and only six to the III) Political tights. Thus the pattern already visible in the subcategory of A) Politics, history and geography is dominant again – concentration on very descriptive aspects without mentioning functions or rights.

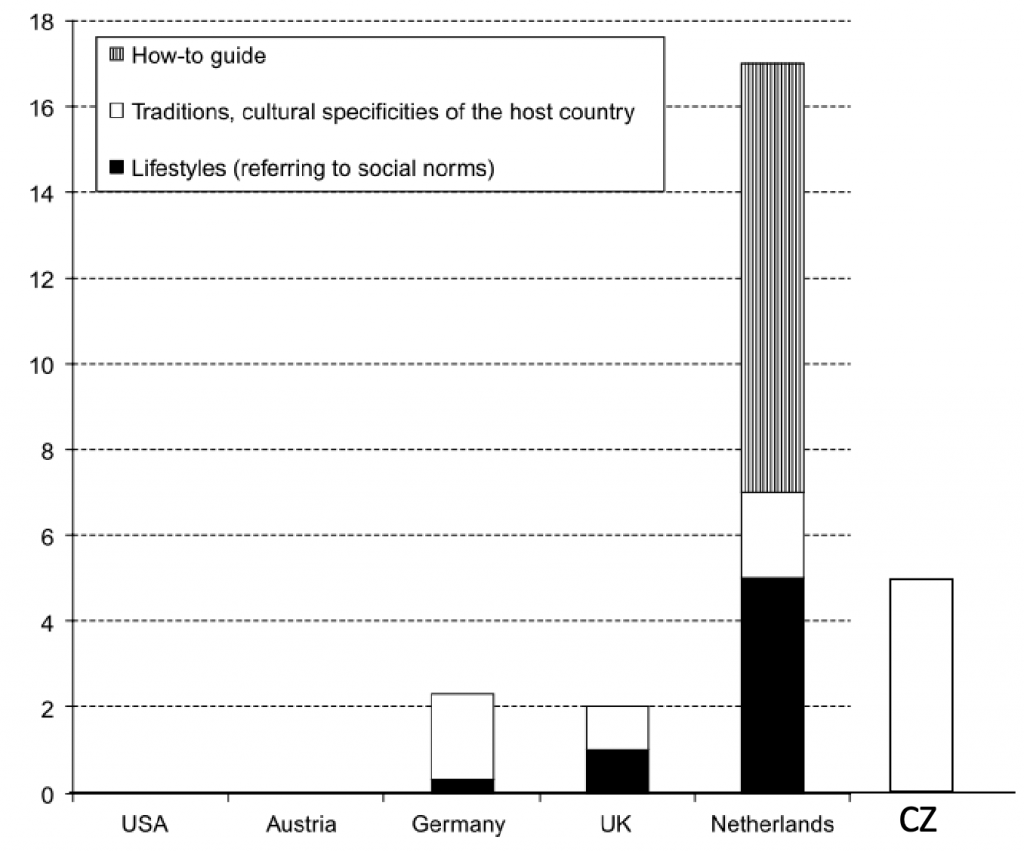

The last aspect which I would like to discuss assessing the (il)liberal nature of the Czech test is the category C) Traditions and public moral. As you can see in the Figure 3 the Czech test has more questions in those categories than Germany and UK, although less than the Netherlands.

In the Czech test there are no questions in the subcategory of 1. How-to guide suggesting how is it proper to behave and there are no 2. Lifestyle questions referring to social norms (such as the Dutch question that cohabitation of homosexual couples is a social norm). Striking is that in the Czech test the highest number of questions is in the subcategory 3. Traditions, cultural specificities, which is higher than in the Netherlands and even Germany.

Those five questions ask about: 1) on which holiday “women and girls give men eggs?” (Eastern), 2) when is the All Souls’ Day celebrated, 3) on which day Czechs usually give each other Christmas presents, 4) who brings sweets to children on 5th December (St. Nicolas) and 5) who brings presents on Christmas. The last question provides those answers: A. Grandfather Frost, B. Baby Jesus, C. St. Nicholas, D. Santa Claus. Grandfather Frost was a tradition imposed by the Soviet Russia during communism and is hold by Russians who are among the biggest naturalisation groups in the state. The right answer that Baby Jesus brings presents tends to highlight belonging to the Roman Catholic tradition although only 10% of population stated they are Roman Catholics but whole 35% that they have no religion (CIA.gov 2015).

Summary

To sum up, after presenting the theoretical debate about how (il)liberal are citizenship tests I used Michalowski’s (2011) content analysis on the Czech test. The context of the test introduction was of “a restrictive liberalization” (mipex.eu 2012) and that is also reflected in the content of the test.

on the other hand the test is mostly concerned with descriptive aspects of history and geography and even the questions about political system are only describing institutions – which resembles “memorization of random trivia” which for example the US tried to overcome

On one hand all 300 questions and answers are freely available and the test success is around 90% (idnes.cz 2014), on the other hand the test is mostly concerned with descriptive aspects of history and geography and even the questions about political system are only describing institutions – which resembles “memorization of random trivia” which for example the US tried to overcome (Orgad 2011). Thus the Czech test for sure can be seen as a substitute for the Czech education (in line with Joppke’s [2010b] minimalist position). Unfortunately the test repeats also negative aspect of the Czech education: heavy emphasis on accumulation of facts without putting them into context or understanding their meaning. For sure the test does not indicate that the Czech state understands that naturalisation procedure of a new citizen as his/her stepping into the polity of the state. It does not tell almost anything about political rights – only six questions (2%) are concerned with political rights, which are the biggest factual gain in comparison to a permanent residency.

The test concentrates on geographical, historical, administrative and institutional description and omits even the appropriate legal description of rights, not to speak about empowering citizens to use the newly gained rights and the full membership in the Czech polity.

The test concentrates on geographical, historical, administrative and institutional description and omits even the appropriate legal description of rights, not to speak about empowering citizens to use the newly gained rights and the full membership in the Czech polity. It seems that the Czech citizenship test is in its content mostly liberal. On the other hand the text of explanatory memorandum requiring “acceptance of cultural traditions” is clearly illiberal and shows the underlying logic which with high probability informs also the process of acquisition of the Czech citizenship.

References

- CIA.gov (2015) The World Factbook – Czech Republic https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ez.html (9/12/2015)

expats.cz (2014) - Who Wants to Be a Czech Citizen? http://www.expats.cz/prague/article/czech-language/who-wants-to-be-a-czech-resident/ (18/11/2015)

idnes.cz (2012) - Cizincům se vzdálí šance na české občanství, kritici se bojí moci úřadů,

http://zpravy.idnes.cz/neziskovky-kritizuji-zakon-o-statnim-obcanstvi-fu7-/domaci.aspx?c=A120222_151817_domaci_jj (18/11/2015)

idnes.cz (2014) - Zájem o české občanství letos prudce vzrostl, uspěly už tisíce cizinců http://zpravy.idnes.cz/zadatelu-o-ceske-obcanstvi-vyrazne-pribylo-fk9-/domaci.aspx?c=A140820_193433_domaci_jj (18/11/2015)

- Michalowski I. (2011) Required to assimilate? The content of citizenship tests in five countries, Citizenship Studies, 15:6-7, 749-768, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2011.600116

- migrationonline.cz (2013) New law on the acquisition of Czech citizenship: introduction to the main changes valid as of January 2014 http://www.migrationonline.cz/en/new-law-on-the-acquisition-of-czech-citizenship-introduction-to-the-main-changes-valid-as-of-january-2014

- mipex.eu (2012) A restrictive liberalisation? Czechs follow EU trends on citizenship http://www.mipex.eu/blog/a-restrictive-liberalisation-czechs-follow-eu-trends-on-citizenship (28/11/2015)

- obcanstvi.cestina-pro-cizince.cz (2015) DATABANKA TESTOVÝCH ÚLOH Z ČESKÝCH REÁLIÍ, http://obcanstvi.cestina-pro-cizince.cz/uploads/Databanka_testovych_uloh_z_ceskych_realii.pdf (18/11/2015)

Orgad, L. (2011) Creating new Americans: The essence of Americanism under the citizenship test. Houston law review, 47(5). - praguepost.com (2015) More foreigners get Czech citizenship http://www.praguepost.com/czech-news/49516-more-foreigners-get-czech-citizenship (28/11/2015)

- radio.cz (2012) NGOs criticize draft bill on Czech citizenship as too harsh on immigrants http://www.radio.cz/en/section/curraffrs/ngos-criticize-draft-bill-on-czech-citizenship-as-too-harsh-on-immigrants (28/11/2015)

Chapters from the EUI working paper

Rainer Bauböck and Christian Joppke, eds. How Liberal are Citizenship Tests? EUI Working Papers RSCAS 2010/41, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, Florence, 2010. http://eudo-citizenship.eu/docs/RSCAS_2010_41.pdf ( 18/11/2015) – following chapters:

- Joppke Ch. (2010) How liberal are citizenship tests?

- Michalowski I. (2010) Citizenship tests and traditions of state interference with cultural diversity

- von Koppenfels A. K. (2010) Citizenship tests could signal that European states perceive themselves as immigration countries

- Kostakopoulou D. (2010) What liberalism is committed to and why current citizenship policies fail this test

- Liav O. (2010) Five Liberal Concerns about Citizenship Tests

- Carrera S. and Guild E. (2010) Are Integration Tests Liberal? The “Universalistic Liberal Democratic Principles” as Illiberal Exceptionalism

- Carens J. (2010) The most liberal citizenship test is none at all

- Christian J. (2010b) How Liberal Are Citizenship Tests? A Rejoinder

- Groenendijk K. and van Oers R. (2010) How liberal tests are does not merely depend on their content, but also their effects